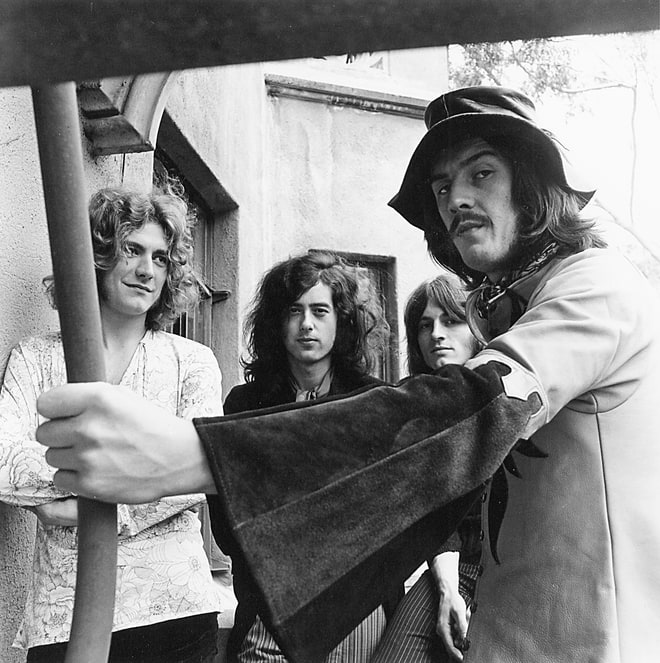

John Bonham

On the very first cut of the very first Led Zeppelin LP, John Bonham changed rock drumming forever. Years later, Jimmy Page was still amused by the disorienting impact that "Good Times Bad Times," with its jaw-dropping bass-drum hiccups, had on listeners: "Everyone was laying bets that Bonzo was using two bass drums, but he only had one." Heavy, lively, virtuosic and deliberate, that performance laid out the terrain Bonham's artful clobbering would conquer before his untimely death in 1980. At his most brutally paleolithic he never bludgeoned dully, at his most rhythmically dumbfounding he never stooped to unnecessary wankery, and every night on tour he dodged both pitfalls with his glorious stampede through "Moby Dick." "I spent years in my bedroom – literally fucking years – listening to Bonham's drums and trying to emulate his swing or his behind-the-beat swagger or his speed or power," Dave Grohl once wrote in Rolling Stone, "not just memorizing what he did on those albums but getting myself into a place where I would have the same instinctual direction as he had." This was a course that nearly every post-Bonham rock drummer would follow at one time or another, a quest that allowed the greatest to eventually find their own grooves.

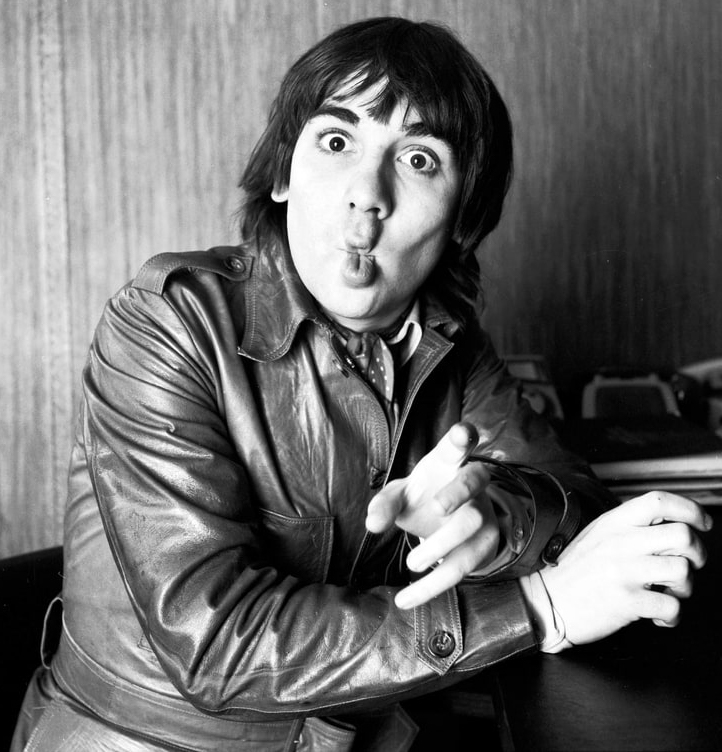

Keith Moon

The "greatest Keith Moon-type drummer in the world," as he described himself, abhorred the repetition of rote rock drumming – as well as the repetition in life in general. Moon, the inspiration for the Muppets character Animal, smashed drum kits and hotel rooms with a ferocity suggesting he was more performance artist than mere rock "sticksman." He famously refused to play drum solos and instead treated drums as the Who's lead instrument. "His breaks were melodic," bassist John Entwistle told Rolling Stone, "because he tried to play with everyone in the band at once." Moon the Loon fit drum rolls into places they were never intended to go and only the synth tracks used on Who's Next stabilized his constantly wavering sense of tempo. "Keith Moon, he’s really orchestrated, like a timpani player or a cymbal player in an orchestra," said Jane's Addiction's Stephen Perkins. "He’s making you know that this is an important part, even though it might not be exactly at the end of the four bars. I love that drama, that theater and I love the emotion." Moon's favorite stunt, though, was flushing powerful explosives down hotel toilets, a trick he pulled until 1978, when he died from a drug overdose at age 31.

Ginger Baker

Gifted with immense talent, and cursed with a temper to match, Ginger Baker combined jazz training with a powerful polyrhythmic style in the world's first, and best, power trio. While clashing constantly with Cream bandmates Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton, the London-born drummer introduced showmanship to the rock world with double-kick virtuosity and extended solos. Following the breakup of the short-lived Blind Faith, Baker moved to Nigeria for several years in the Seventies. "He understands the African beat more than any other Westerner," declared Afrobeat co-creator Tony Allen. In the years since, Baker has kept busy with an impressive array of projects, flaunting his signature bravura, intricately braided grooves in undervalued mid-Seventies venture Baker Gurvitz Army, jazz combos featuring star soloists like Bill Frisell, and compelling collaborations with Public Image Ltd and Masters of Reality.